Paths of Most Resistance

Paths of Most Resistance

How Trail Crews Fight the Forest in Olympic National Park

By Ted Alvarez Originally Published in BACKPACKER MAGAZINE, July 2016

Don't let the manicured paths trick you: Workers in Washington state's mountains wage an endless war to keep the trails open.

Don’t believe the guidebooks or gorgeous photos: Olympic National Park doesn’t want you. Nine months a year, the wilderness acts like a malevolent force bent on keeping hikers from ever setting foot there. Its near-8,000-foot peaks haul in storms off the North Pacific, howlers weaned on the Arctic and teethed on Alaskan sea ice. When the peninsula’s spiky geology embraces clouds, it wrings out the most precipitation in the Lower 48: 30 feet of snow up high, 150 inches of rain down below. Biology can’t withstand the weather. Old-growth Sitka spruces 8 feet in diameter bow and then break under winter gales, and rivers, churning with mountain-shearing force, plot new watercourses through temperate rainforest, siphoning tons of rock and vomiting them into meadows. A single season’s worth of meteorological warfare can vaporize bridges and bury miles of switchbacks under quick-churned biomass.

Right now, I’m looking at a tiny example of what that power can do to a trail. Well, relatively tiny. There’s a 60-foot tree with a rootball the size of a FedEx truck blocking the East Fork Quinault River Trail a quarter-mile from my camp. The trail is impassable; it’s choked with mud, dangling ferns, and rocks mashed into the rootball. The whole mess is tethered to the mountain by tenacious roots.

Few hikers will make it up the East Fork Quinault this year if this rootball remains in place. But it won’t. Every March, Olympic National Park trail builders take on the monumental task of rebuilding perhaps more miles of trail than any other crew in the country. Chainsaw bushwhackers swarm the hills like ants, crack helicopter pilots surgically remove broken bridges, and trail planners plot workarounds where a river has rerouted a valley. But first, four of its finest are going to move this damn tree.

“In theory, the beast should move,” Olympic trail crew leader Lynn Gunther shouts, leaning his burly frame to peer at the teal rapids 200 feet below. “We’ll rig the tree so as he saws it off it will roll downhill by itself, hopefully into the river. If it doesn’t … Well, it’s going to be interesting.”

Despite being visible from Seattle, the interior of Olympic resisted gold rushes and ages of exploration until 1889, when a Seattle newspaper called for “hardy citizens … to acquire fame by unveiling the mystery which wraps the land encircled by the snow-capped Olympic range.” Six men launched the Press Expedition, along with two mules, four dogs, and a flat-bottom boat meant to ferry 1,500 pounds of supplies. The boat sank. Both mules died. An elk killed a dog. Shattered and starving on flour soup, the party emerged from the North Fork Quinault six months later.

You can retrace their route now in about four or five days, thanks to a red-carpet trail system. No roads penetrate the core of the park. The only way to see it is on foot, and since the park’s inception as a monument in 1909, the NPS has employed hard-as-nails trail crews to thread paths through a remarkably fast-growing and turbulent ecosystem. Most of them rely on little more than hand tools, mules, and the occasional chainsaw. Though helicopter assists happen, they were more common in freewheeling yesteryear before the park curtailed flights to keep from disturbing the wildlife.

“In the old days, you could fly in on a helicopter, show up at the top of a pass, and bring in a basket of oysters and a bucket of beer,” Gunther recalls. “I miss it a bit.”

Like Gunther, Larry Lack comes from this leathered tradition. The Olympic National Park trail supervisor has spent 37 of his 55 years repairing these paths, ensuring the public has access to the sky-high trees, alpine meadows, and glaciated peaks in the roadless 1,442-square-mile interior. His open-air office in Port Angeles is halfway to a mechanic’s garage and bears the relics of a trail grunt who has risen to general: rusting, 8-foot saw blades hang on the walls next to beat-up trail signs.

“I ran mule pack strings for 14 years and then somehow worked my way into a desk job. I miss being in the field, but I’m not sure my body could do it anymore,” he says with a rasp. “But I grew up in Port Angeles -- the park is my backyard and I take pride in showing it off to people, providing access, and making it a little bit easier to get back there and enjoy it.”

Bearded and blue-eyed, he’s seen the Olympics at their angriest. A glacial river once shifted and buried a 12-foot-tall backcountry shelter, leaving only a few inches at the peak of the roof poking out of the gravel bar. Once, a bank blew out and gully-washed a steel bridge; one 70-foot steel I-beam just up and disappeared. Even building a sidehill trail in the rainforest means digging through 5 or 6 feet of forest duff and rotten wood—and that’s if you can cut through salmonberry bushes that grow 12 feet a year.

“Come spring, we have the most devastated trails in the park system,” says veteran Hoh Rain Forest-area interpretive ranger Jon Preston. “It looks like bombs went off.”

These are the hardest trails to clear in America, and this was not a good year. Nearly 13 feet of rain fell between October 1 and mid-March alone. The Quinault River swelled so much, the historic Enchanted Valley Chalet was close to collapsing into it; the park flew in a construction crew to lift the 86-year-old shelter with hydraulic jacks and slide it on steel beams 100 feet away from the river. Starting in late March, Lack broke into this year’s $1.3 million budget to fix as much trail as possible before 4 million people swarm our seventh busiest park this summer. There are 611 miles of trail in Olympic and Lack estimates his assemblage of 70 volunteer, seasonal, and fulltime workers can clean up to 500 in a season.

“It’s a challenge. It seems like you spend all summer getting the trail in shape and about the time you’re done, Mother Nature comes in and rearranges everything again,” Lack says.

That’s the story behind every easy, taken-for-granted mile of trail in the park. Crews spend their summers scratching detailed plans in the dirt, tugging on white-shirt higher-ups for pennies, and blowing hours and rivers of human sweat to earn back a few miles of trail for an oblivious public that thinks they pick up trash for a living. As they finish, rain drops let them know an engorged ecosystem is about ready to shake the Etch-A-Sketch on their life’s work. Again.

But without them, it’d be a lot harder to see much of the parks.

How Do We Make the National Parks More Diverse?

How Do We Make the National Parks More Diverse?

By Ted Alvarez Originally Published in BACKPACKER MAGAZINE, July 2016

Everyone agrees park visitors should better represent our country’s diverse population. Four experts weigh in on how we can break down the barriers.

More than 307 million people visited national parks in 2015, shattering records and setting up the system we love for a banner Centennial. The problem? Seventy-eight percent of those visitors where white. That doesn’t bode well for a country that will be mostly nonwhite by 2044.

Park system officials recognize the challenge. “If I were a business and that were my clientele,” says NPS Director Jonathan Jarvis, “I wouldn’t be in business for much longer.”

The just-launched Centennial Initiative will unite 30 conservation, civil rights, and environmental justice groups in an effort to increase diversity in national parks.

That’s a start, but it will take much more to ensure that every American, regardless of race, creed, or background, sees the parks as his or her birthright. We convened some of the key thinkers in this effort to get their opinions on how to really make the parks for everyone.

Teresa Baker

Founder, African American Nature & Parks Experience

If we provide opportunities, demand is there: “In 2013, I went on Facebook and created a single African American National Parks Event. The sole purpose was just to engage people; it was going to be a one-time thing to bring people out to Yosemite. Now, this will be the fourth year in a row I’ve done African American National Parks events in the first weekend of June.”

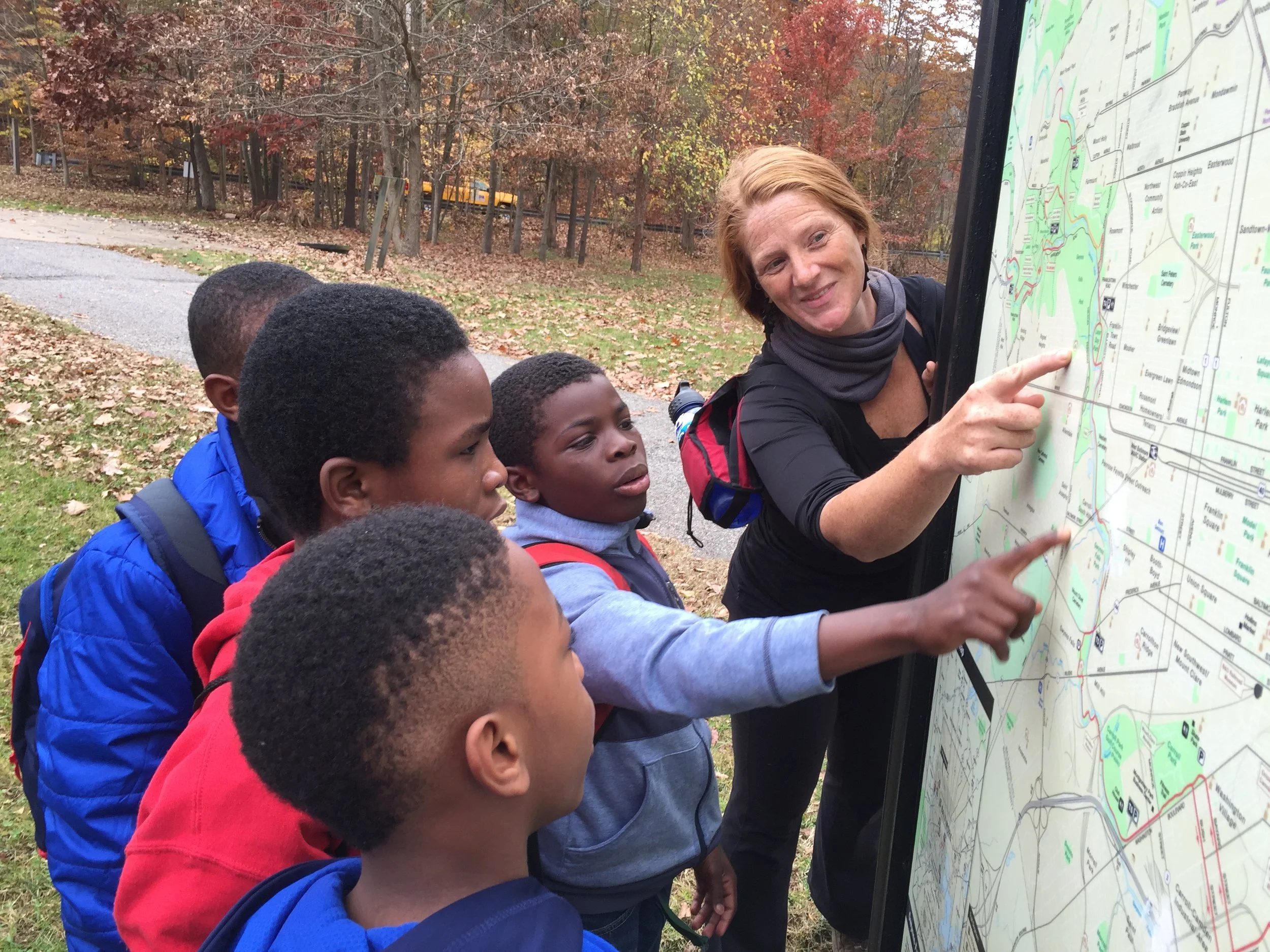

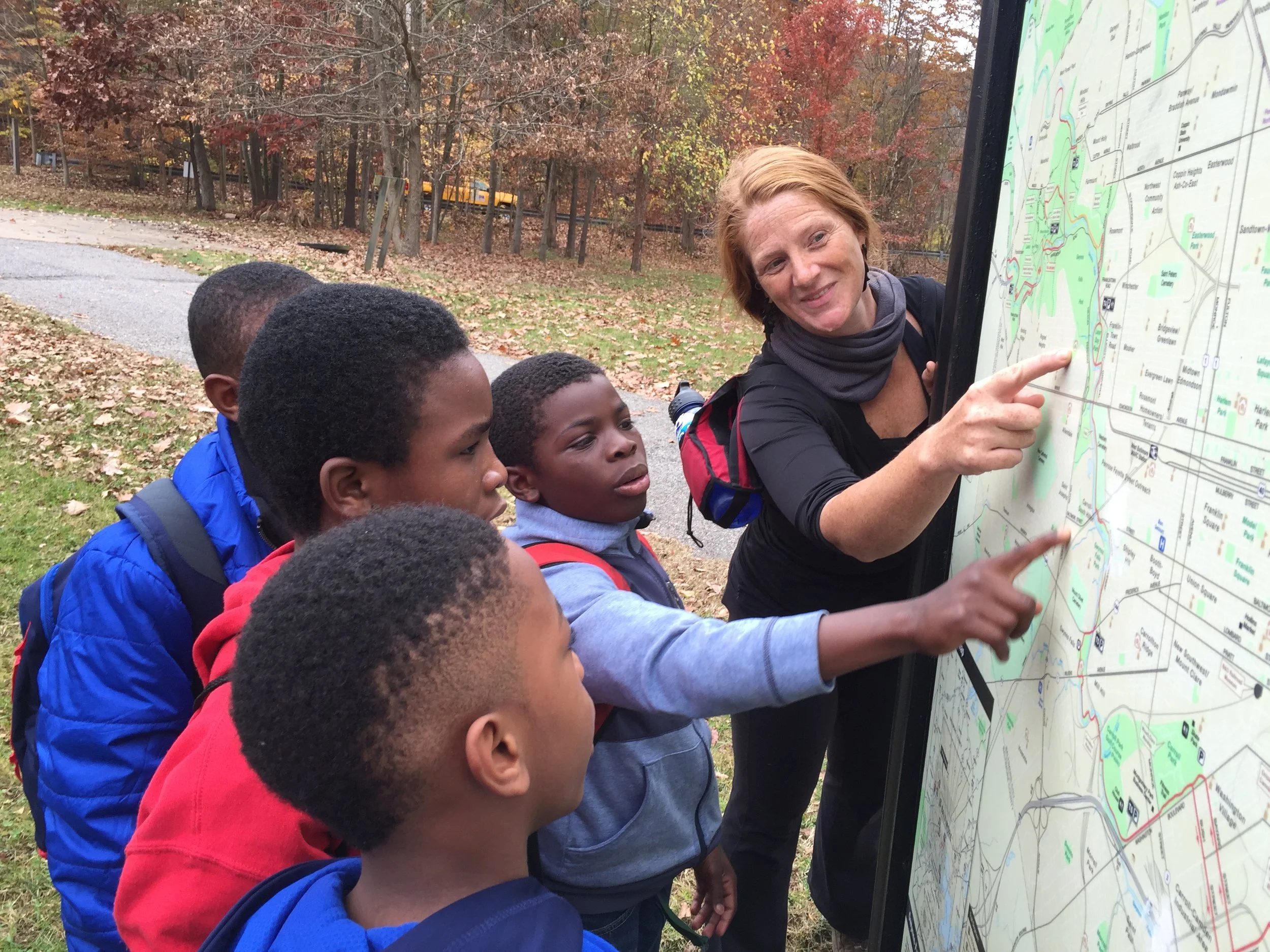

Meet the people where they are: “A huge opportunity we are missing is partnering with city parks to become more visible in the outdoors. Folks here have never seen a ranger uniform. If the National Park Service partnered on a city hike with a ranger, that would bring more exposure and that’s what’s needed.”

Make first-timers comfortable: “I get a lot of people who ask ‘how do we prepare for our first camping or hiking trip?’ I tell them to give me the name of the campground and I will personally reach out and put them in touch so [a ranger] can give them a quick tour of the campground or trail, tell them what they can expect. A lot of these places, you’re not going to see a ranger who looks like you. But if you have a name and know someone is going to be waiting to have a conversation and greet you, that helps a lot.”

Glenn Nelson

Founder of The Trail Posse, a website dedicated to documenting and encouraging diversity in the outdoors

Help people see themselves in the parks: “I’m trying to change the picture by showing people of color in the outdoors. We may call them public lands, but to a lot of people they look like an exclusive country club [in the mainstream media]. The NPS is doing this massive Find Your Park campaign for the Centennial, but I wonder if communities of color see this. Did they look into reaching African Americans through the church or Latinos through radio?”

There are many ways to get there:“My wife is an inner-city L.A. native, a Latina. So how did I get her interested [in the outdoors]? We bought our first house and bought a bird feeder, and we were attracting northern flickers, became attached, replanted our yard with native habitat, got a pair of binoculars, started traveling to wildlife refuges and parks for birdwatching. It blossomed out of the simple act of looking up in the sky.”

Prof. Carolyn Finney

Assistant professor of cultural geography at the University of Kentucky, author of Black Faces, White Spaces: Reimagining the Relationship of African Americans to the Great Outdoors

Don’t believe the myths: “Black people don’t go hiking. Black people don’t paddle. Those are myths. We do everything like everybody else, though our experience may be circumscribed. Think about Jim Crow segregation—that’s going to limit your ability to go outdoors. Nevertheless, Rue Mapp and Outdoor Afro is big. Groups like that are really getting black folks into the outdoors. There are hundreds that do this. And you have examples like the black mountain climbing team that did Denali and Audrey and Frank Peterman, who went across the country going to national parks.”

Bring it home: “It’s not just about places where we go far away—it’s about loving where we are. Nature is here and now. A number of years ago, I visited an afterschool program. Many of these kids have never gone camping, so we took them camping in Rock Creek Park [in Washington, D.C.]. One or two of them said that in coming home, they noticed the garbage on the street in ways they didn’t notice before, and they’re like ‘How come this place doesn’t look really nice? What do we need to do about that?’”

José González

Founder and director of Latino Outdoors

Recognize differences:“Part of my work is to celebrate the diversity within the Latino identity. It’s different in Texas, California, or New York. There are common markers—family, respect, value of culture. But in one area, the Latino community is professional and middle class, and they’re looking for opportunities to camp. In other places, they might have experienced city parks, but they have never had the need or income to go get a tent.”

Every experience counts: “We were taking a group of families to the closest state park, about 20 minutes away here in California. We had a dad dressed in his Sunday best—because we said ‘Sunday at the park with your family.’ But this was a ‘repair an ecosystem’ day with digging in the dirt. But was he OK in terms of safety and comfort? Yes. So we didn’t say, ‘You aren’t dressed the right way.’ At the end of the day, he played a guitar and sang about parks. It might have been the first time he’d gone to a place that’s so different, but we open up the cultural familiarity so he knows ‘who I am and what I’m bringing is acceptable here.’ And we were having pan dulce, mole, and nopales under the sequoias—which was amazing.”

Gear Review: Monkii Bars

Gear Review: Monkii Bars

Monkii Bars Make the World Your Gym—And Playground

By Ted Alvarez Originally Published in OUTSIDE, September 2016

Ignore the goofy spelling: This gadget is a great way to incorporate high-octane bodywork into any outdoor adventure.

School kids never ask to sub on a bench press set or draft you on a trail run. But everywhere I take my Monkii Bars—city park, Cascade foothill, national park—there’s a goggly-eyed tyke asking if she can mimic my dips, try an archer push-up, or just swing around like a gibbon. I let them, but they usually only get a few minutes before a jealous parent butts in to give it a go.

I can’t blame them: Monkii Bars are fun as hell. But all that primate whimsy doesn’t detract from the suspension system’s impressive ability to turn the outdoors into your full-service bodywork gym. The original version launched in 2014, and I used it to keep fit everywhere from fridge-size hotel rooms in New York City to the shores of an iceberg-filled lake in Patagonia’s Los Glaciares National Park. According to company founders, over 3,000 customers have soldiered into the woods with Monkii Bars since its debut.

The next version of Monkii Bars launched via Kickstarter on July 11, and will eventually include an app cataloging over 250 custom workouts, geolocated workout spots all over the world, and user-submitted training programs from the growing Monkii Bars community.

Here’s a video of Monkii Bars co-founder, former wilderness ranger, and Tarzan lookalike Dan Vinson showing them off:

https://youtu.be/XAETT1BJSmM

I’ve been testing the mid-size Monkii Bars 2 Adventure Kit for about a month, putting it through its paces. Here are my initial impressions.

The concept remains basically the same. Two hollow, nunchuk-size bars with plastic endcaps contain connector straps inside. Sling an 18-foot length of nylon webbing over a sturdy tree limb or the top of a closed door using a specialized door attachment, thread the webbing through the connectors, and voilá—instant gym. Just add sweat.

Version 2 features a few major improvements. Half-inch nylon webbing replaces thin Spectra cord, and a simple friction lock vastly improves on the hook-and-eye adjuster from the old version. Looping the spaghetti-thin Spectra cord into and around the old adjuster was a tricky affair for nonclimbers: I toppled to the ground once or twice when the cord slipped after I hadn’t looped it enough times. Now I just thread the webbing and let the lock snap in place. It's simple and bomber. The new webbing also doesn’t fray at the ends or cut into your arms like cheesewire when you accidentally press against them mid-dip.

The U.S.-made, nine-ounce bars are made of powder-coated aluminum and come in a Skittles array of colors. While I miss the organic, yoga-studio look of the bamboo-only originals, the new versions offer better durability and grip under sweaty palms. The addition of connector straps (rather than having the entire 18-foot length of Spectra cord run through the hollow bar) also makes Monkii Bars 2 more stable than before.

Unfortunately, all that new functionality comes at the cost of packability. Previously, the entire Monkii Bar system—Spectra cord, hook-and-eye adjuster—fit inside each bar. The webbing slings and friction locks won’t, so even the ultralight version requires a minimal case to strap them to the outside. With the previous iteration, it was so convenient to toss the bars into my pack, even if I didn’t know where I would end up, just to have the opportunity to workout somewhere wild and interesting. (Then again, the two individual bars were frequently mistaken for pipe bombs by TSA inspectors—the new Monkii Bars are TSA-approved.) Still, the Adventure Kit I used wraps into a sleek folding case about the size of an extra-large burrito. It weighs about 25 ounces total, and has extra features like a cellphone holder, so you can watch workout demos, and stirrups for exercises like suspended planks and mountain climbers. The case itself doubles as the door attachment.

But hold the door. Unless it’s raining bullets or you’re trapped in a Hanoi hotel room, these babies are best outside. There’s nothing quite like setting a lazy Sunday city run afire by capping it with some upper-body work at a random tree or rewarding yourself for breaking your own muscle-up record with a dive in an alpine lake. Performing bodywork while suspended means you’re also doubling up on balance, core, and fast-twitch strength, too. Monkii Bars are still one of the most fun ways to do all that—and make friends with a bunch of rambunctious 8-year-olds while you’re at it.

Monkii Bars 2 kits start at $119 and are available for preorder on Kickstarter.

The Truth About Bears

The Truth About Bears

SPECIAL REPORT: THE TRUTH ABOUT BEARS

By Ted Alvarez Originally Published in BACKPACKER MAGAZINE, February/March 2013

Oso. Xiong. Bruin. Bjorn. Bear. From Cro-Magnons to Colbert, humans of all cultures have been obsessed with bears since we started competing for cave space. Backpackers know why better than most: As both slideshow highlights and boogeymen, bears remain the most potent reminder of our primal connection to the wild—and our place in it. Over the years, we’ve alternately feared, worshipped, or exterminated them. But new, myth-busting science allows us to know them better—and stay safer—than ever before. This is the story of how bears are coming back, and why that’s good news for us, too.

We run into a bear at the end of our first day looking for grizzlies in Washington’s North Cascades National Park. Unfortunately, it’s the wrong kind: a runty black, not much bigger than a large Rottweiler, that ambles past our camp at Copper Creek. Probably a few thousand calories short of its daily huckleberry haul, it ignores us without so much as a glance before leaving a splat of half-digested mixed-berry casserole on the trail.

Glossy black fur, Roman nose, big ears: From 30 yards away, there’s no way I’d mistake it for its larger cousin, but it still feels like a good omen. As the bear gains distance in the dimming twilight, it mixes with its own shadow, inflating in my sight as it noses through an electric-green huckleberry understory and past dense trunks of silver fir. It’s easy to believe that if we’re lucky enough to find a grizzly out here, it might look a lot like this. From now on, every movement—a jiggling twig, a fleeting shadow—catches my eye as a potential sign of the Griz.

My odds of seeing one hover only slightly above my chances of high-fiving Sasquatch. Nobody really knows exactly how many isolated grizzlies hide in the tangle of mile-deep river canyons, old-growth forests, city-size glaciers, dragon-tail ridges, and tilted heather meadows that knot together the greater North Cascades ecosystem. It’s a border-straddling wilderness stronghold that’s bigger than Maryland. Since a hunter shot the last grizzly bear here—in Fisher Creek Basin in 1967—the evidence supporting their existence has been largely the same as that supporting Bigfoot’s: split-second glimpses from a distance, secondhand accounts, and errant footprints leading toward cryptozoological myth. Without any physical or photographic evidence, hopeful biologists and conservationists subsisted on a slow trickle of dubious sightings, sometimes several years apart. A 14-year drought after 1996 convinced many that the Cascades grizzly was nothing but a legend.

But then came the miracle photo: In October 2010, a hiker snapped a shot of a fat, healthy grizzly near Cascade Pass, too far south to be a Canadian bear on a work visa. It was the first confirmed photo of a live grizzly in the North Cascades in almost 50 years: a Loch Ness-caliber money shot.

The photo dropped a month after I moved to Seattle, and the sheer wonder of it floored me like images from a Mars rover landing: grizzlies! A mere two-and-a-half hours from a major metropolitan area, closer than anywhere else in the country! Two years later, I’m still hopped up on possibility—and so is Bill Gaines, an independent wildlife ecologist and U.S. Forest Service veteran. He serves as a principal investigator for the Cascade Carnivore Connectivity Project, a joint effort between academia and government aimed at mapping how carnivores move and breed between ecosystems, and how roads affect their conservation and recovery. The photo poured gasoline on the group’s most ambitious project yet: a three-year survey funded by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service targeted at determining the status of the grizzly population and its potential recovery. The USFWS has a mandate to support recovery efforts for every endangered species—but it can’t even make baby steps until biologists know how many animals they’re dealing with, and thus how best to proceed. For Cascade grizzlies, that number is still a blank.

“I am cautiously optimistic,” says Gaines. “That photo was pretty exciting. But it’s like looking for a moving needle in a haystack. Three haystacks, actually—there’s a lot of luck involved.”

He and others have been searching for grizzlies here since the late 1980s. They believe Cascade grizzlies should be a wildlife conservation cause célèbre, like Yellowstone’s wolves in the 1990s. While grizzly populations boom in other Lower 48 recovery zones, Cascades grizzlies barely hang on, despite having access to arguably the best habitat. We pushed bears so deep into the wild that they backed into a genetic bottleneck, where fragmented populations face grim prospects for breeding, or even finding each other.

And yet they survive. Biologists believe as many as 20 grizzlies persist in Washington’s Cascades, though pessimists (realists?) would peg that number closer to five. Another 20 or so live immediately north of the border, and their ranges overlap. Rather than reintroduce the species, bear biologists have the rare opportunity to preserve and extend an original grizzly genetic line that reaches back millennia. A romantic might even say restoring bears to their full might here, in one of the final spaces we’ve left for them, goes a little way toward atoning for centuries of persecution.

A romantic would be disheartened by the progress so far. In two years of searching, Gaines has failed to turn up so much as a grizzly eyelash. But where past surveys featured a mix of road- and trail-accessed sites, this third and final season, Gaines’s research team has refined its focus; they’re boring into the trackless, inaccessible heart of the park on foot, research equipment stowed in hulking packs. I join Gaines and two of his colleagues for their final trip of the project: a 50-mile push up and over Hannegan Pass, down into the Chilliwack River basin, and up to basecamp on obscure Easy Ridge via little-used climbers’ paths. From there, we’ll abandon even the semblance of trails for interminable bushwhacks across sketchy slopes until we drop off the edge of the world. It’s the last place a human should be, and therefore the perfect place to find our ghost grizzly.

Continue Part 1: The Mystery: Their Resurgence

Part 2: The Maps – Where to Find Bears

Part 3: The Skills – How to Prevent an Attack

Best Discovery: Hai Country, Japan

Best Discovery: Hai Country, Japan

BEST DISCOVERY: HAI COUNTRY, JAPAN

By Ted Alvarez Originally Published in BACKPACKER MAGAZINE, November, 2013

"When Daisetsuzan bites, she bites very hard."

The guide’s words from yesterday—about the park in which I’m now hiking solo—rattle in my ears as I watch a fogbank barrel up a forested valley 3,000 feet below. It leaps over a banded cliff, races across tundra, and blows in my face, mixing with the haze rising off the 35-degree remnant snowfield I’m picking my way across. Vast mats of flowers in magenta, indigo, and pale yellow blink off like Christmas lights into the murk.

Then I hear thunder kettledrum in the clouds above and behind me.

I scamper across the remainder of the ice and duck under a 2-foot-tall hedge of Siberian dwarf pine to pull out my topos, labeled with ornate and indecipherable Japanese kanji characters. I rotate the map several times before I get my bearings. The near-vertical, jumbled ridge I’m supposed to scramble down next, in my attempt to traverse the park, presents in person as a flat, gray wall. On the map, the now-departed guide left an English tip in cute, bubbly handwriting: “Rock-Garden!!! Caution when visibility is unwell.” The wind steals my string of expletives. I came looking for wild. I’ve definitely found it—but Daisetsuzan is biting now, and it hurts.

There is no real word for "wilderness" in Japanese. This is, after all, one of the most densely populated countries in the world; certain spots cram more than 11,300 souls into a single square kilometer of towering concrete and blinking neon. There's a countrywide fetish for suturism and robots, and the people have a reputation for buttoned-up formality.

Yet mountains, forests, and meadows cover 67 percent of Japan’s landmass. The rhythms of the wild suffuse traditional culture, from the animist Shinto religion to modern doctors who prescribe “forest bathing”—hanging out in the woods—to prevent cancer. But the porous border between man and wild has a downside: Japanese nature often seems civilized and manicured, with networks of teak-floored inns and gondolas spooling up every peak. It means every spring millions of Japanese flock to the mountains for hinami (“flower viewing”)—and some bring tea sets that match their gaiters.

I can’t fault their enthusiasm: Japan’s mountain ranges—kissed by volcanic fire, flushed with endemic flora and fauna—are wholly unique to the islands. And the country’s first-rate infrastructure means you can step into the primeval from the edge of a bullet train platform. I find the contrast irresistible—but more importantly, I’m convinced I’ve found a secret stash of honest-to-god, true wilderness in Hokkaido, Japan’s northernmost and least-densely populated major island.

Daisetsuzan National Park is the country’s oldest and biggest preserve. Brutal winters plus some of the deepest snowfalls in the world make the growing season exceptionally short, cultivating swaths of treeless, subarctic tundra at relatively low elevations. The core looks something like Denali with volcanoes in place of glaciers, or a Scottish highlands where all the flowers have gone Seussian.

Hokkaido’s Siberian tinge makes it a bit of a wild enigma even to the Japanese. Japan’s only indigenous tribe, the Ainu, thrived here and conjured up a dense mythology of deities, demons, and lesser spirits who inhabited every stone and stream in Kamuimintara—God’s playground. The corporeal vessels for all those Ainu spirits still haunt the landscape: foxes, Ezo deer, white-tailed sea eagles, a fuzzy-cute raccoon dog called a tanuki, and, most impressively, Ussuri brown bears—biological relics from when Hokkaido was connected to Russia by a now-submerged land bridge.

My goal: Complete the Daisetsuzan Grand Traverse, a 42-mile, five- to seven-day route rambling over the park’s highest peaks and connecting up to nine high-country huts. Besides serving up the park’s best sights, biggest wildlife, and toughest trails, the middle miles fend off vacation-poor, weekend-warrior salarymen and elderly hikers wary of the area’s lack of signage and intimidating routefinding. If my beta is correct, it’ll be a lot like having five days on a bunch of Fourteeners to myself—but with fewer altitude issues and more authentic ramen.

Before I can journey into the unspoiled stuff, though, I have to navigate urban Japan’s neon-lit crush, which includes robo-toilets with 15 oscillating bidet options. By the time I mistakenly feed my bus ticket into the money slot and fluster even the unfailingly polite Japanese passengers behind me, I’m ready to hide my shame in Hokkaido’s inaka—“the boonies.”

The island’s verdant farmland throws me off at first: On the bus from regional hub Asahikawa to the park, rice fields fly past in parallax and clusters of quaint farmhouses sport cabbages bigger than dogs. It has a bucolic beauty, but with the mountains socked in, I can only hope rising welts of forest on the horizon are a sign of wilder things to come.

Water & Oil

Water & Oil

WATER & OIL: HOW NATIVES & NEIGHBORS OF THE SACRED HEADWATERS BATTLED DRILLERS AND WON

By Ted Alvarez Originally Published in GRIST, December 2013

I’m helicoptering over a thousand-mile mess of dirt-dusted glaciers, spongy tundra, and bristling forest in the far north of British Columbia. My gut wobbles as we drop past mountain ridges toward our destination: a soupy, pea-green bog dotted with a handful of black ponds. Fed by whitewater trickles draining the peaks around us, it’s a sucking, primordial muck reminiscent of an antiquated dinosaur mural, or a day-glo panel from Swamp Thing’s origin issue. And sure enough, it’s the birthplace of something big, ancient, and slippery: the Skeena, Nass, and Stikine — three of the largest salmon rivers on the West Coast, all born here or near here in the Sacred Headwaters.

But the Sacred Headwaters doesn’t owe its growing fame to the chinook, coho, and silver salmon races that have been flapping up these rivers since before the Bering Strait opened to pedestrians. For that, we ultimately must thank what lies buried directly 2,000 feet below: 8 trillion cubic feet of natural gas trapped inside vast beds of coal.

Even distant spectators of climate change news know we hear almost all bummer tunes. Between the Chinese-finger-trap gridlock of domestic politics and moribund international summits always ending with grim predictions and toothless resolutions, avoiding an apocalyptic New Normal seems impossible.

As an increasingly fatigued spectator, I look for any reason to emerge from under my Linus cloud. That’s why I jumped when I heard whispers about a remote community in Northern B.C. — First Nations tribe elders, hunters, loggers, sportsmen, skiers, tar-sands workers, environmental NGOs, parents — who all banded together to dissuade no less than Shell Oil from digging up all that carbon. It seemed like a rare clean win, a satisfying victory in an eight-year fight that kept carbon in the ground and high-fived fish over fossil fuels.

Shocker: The reality is much, much more complicated than that. But with the whole of our country mired in the will-he-or-won’t-he tug of war over Keystone XL, I was tired of being fly-papered into uncertainty and agitation. I wanted to look north for inspiration. And so I went.

Northern B.C. hosts 50,000 people scattered across a landscape bigger than California. Modest hamlets like Smithers and Hazelton last a few stoplights before getting swallowed by Jack London. In the lower 48, the expansionist idea of a wilderness of inexhaustible resource looks painfully naïve to even the most casual observer. Here, taming — or even knowing — the seemingly endless forests, rivers, and mountains escapes the imagination.

Even elementary Loraxers know there’s always an end. And whether trees or salmon, Northern B.C.’s economic destiny bends to the extractive — but what’s available aboveground can’t compete with the value of what’s buried underneath it.B.C. exports nearly $1.4 billion in coal to China alone, and another $516 million in minerals and metals. Factor in Canada’s rogue petrostate aspirations, and by the mid aughts, Northern B.C.’s future as a leading carbon provider seemed all but assured.

In 2004, the B.C. government hit the gas by dangling that 8 trillion cubic feet estimate and calling for bids to issue natural gas drilling rights in a 2,485-square-mile area known as the Klappan. Here, upper Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous sediments 3,608 feet below the earth contain 37 million tons of anthracite coal in 27-foot-thick seams, with natural gas laced between, held in place by briny water. Above rise 7,000-foot mountains, salmon streams, and wildlife corridors for caribou, moose, stone sheep, and grizzly. Getting at the gas would require an“unconventional” technique called coalbed methane extraction. While often lumped in with hydraulic fracturing, this country cousin operates like fracking in reverse. Drill towers puncture rock and earth until they reach the anthracite bands; then they hoover out the groundwater like a syringe draining a cyst. Absent water, the pressure reduces and natural gas flows up the needle.

Without public consultation, the B.C. government granted Shell Canada the bid. The company paid the B.C. government a $9.5 million fee and built three test wells that winter, with plans to build 15 more test wells. If those bore fruit, Shell had plans to create a network of several thousand wells, with 2,200 miles of roads and pipelines spidering out from them across the Klappan.

But those 15 test wells never got built. When Shell returned in January 2005 with heavy machinery to continue exploration, they found the only road in blockaded by elders and members of the Tahltan, a 5,000-strong tribe that has used the area — what they call the Klabona, or Sacred Headwaters — for traditional hunting and fishing since before recorded history. The elders — now calling themselves the Klabona Keepers — camped for months to protest Shell and other interests like Fortune Minerals, and in the process became the spear point for a community on the verge of uprising. Shell had barely pierced the ground, and they’d awakened a sleeping giant.

In Sacred Headwaters territory, you learn pretty fast not to call even the crunchiest green an environmentalist. Today’s carbon crusader might be descended from trappers or outfitters who have bad memories from run-ins with Greenpeace over big-game hunting; in some cases, they’ll have fought back against hunter-hating greenies firsthand. And at the inaugural “Save Our Salmon” rally, they’ll be serving moose chili they hunted themselves, thank you very much.

“I don’t consider myself an environmentalist at all,” says Shannon McPhail, executive director (“for the fancy business card; I’m not the boss of anybody”) of the Skeena Watershed Conservation Coalition, a nonprofit environmental organization formed by concerned locals in response to Shell. Now they function as a bulwark when external interests come knocking a bit too hard or often. “You can’t call us just tree-hugging hippies or knuckle-dragging rednecks. Our organization is a full-on lovechild of the Skeena: If all the hippies, settlers, pols, and rednecks birthed a kid, this is what it would look like.

“We sort of have this balance/common sense approach,” she says. “We live here; we know what happens here; so when industry and government come from Calgary or Victoria, each of us can say, ‘Do you know what it’s like to truck in a winter’s worth of wood?’ We’ve all gone through this evolution — you don’t know who your allies are. When you target one group you alienate people. Some of our biggest allies have been welders in the tar sands, big game outfitters, trappers.”

A sixth-generation native to Hazelton, B.C., McPhail exemplifies this complicated evolution herself. As both a river guide and a welder, she first encountered Shell’s operations in her backyard when she was looking for closer work for herself and her husband, who still works in the Alberta tar sands where they met — “in the belly of the beast,” as she puts it. She equated Shell’s entry into the headwaters with jobs and prosperity — until she learned that local employment would be ephemeral, profits wouldn’t stay in the province, and that coalbed methane extraction could potentially put salmon-bearing streams at risk.

“We are an extraction region — it’s not about opening the door, because that’s already happened,” she says. “This is about the pace and scale of development. We have never wanted to be an organization opposing big development, even though that’s a big part of what we do. But we’re going to look at things really critically, and sometimes we’ll say yes. Now there is too much, in too short a time, and not in a way that benefits these people. All these proposals are interfering with people’s lives in a huge way.”

The biggest way goes back to fins and fur: Assessments by the SWCC, IBM, and others concluded that Sacred Headwaters salmon sustains $110-150 million in retail, fishing, and food value, and another $1 billion in tourism, outfitting, hunting, and associated services. Five hundred permanent jobs are tied to salmon alone, and the relatively low visibility — Northern B.C. has a patchwork of six understaffed provincial parks and no national parks — leaves a vast and unexplored market for adventure and ecotourism.

Carrie Collingwood grew up in that business. The daughter and niece of local outfitting legends Ray and Reg Collingwood (who tussled with Greenpeace and eventually won a court case against them), she helps run their venerable 40-year-old operation, Spatsizi Wilderness Lodge, and runs a fly fishing outfit of her own (Babine Norlakes). By the time Shell Canada arrived, the battle lines were clear.

“Spatsizi (Provincial Park) is protected from resource extraction, but wildlife and salmon don’t follow park boundaries,” she says. “Beyond the contamination to water, for us the biggest concern was definitely the scar across the linear landscape. All the roads, the pathways, the various wellheads over a huge expanse of land — all that gives wolves much easier access to moose and caribou calves. It interrupts migration corridors and affects downstream wildlife — our business.”

But the snowball started by the Tahltan blew beyond business concerns and rolled straight into the heart of the community, picking up momentum and followers of all stripes as it went.

“When I first heard about it I had no idea what was involved,” Collingwood says. “Fracking, drilling, coalbed extraction — I went to open houses to see what was going on. We really got involved right when I realized the magnitude: It wasn’t like just it’s not good for our business. When we discovered this isn’t good for anybody, we started working with the Tahltan with wildlife monitoring on the Klappan. We ended up creating the Spatsizi Heritage Fund, and all the money that we raised, we turned around and supported the Tahltan.”

Anthropologist, writer, and National Geographic explorer-in-residence Wade Davis is among those who have shouted for the Tahltan loudest and longest. He’s lived seasonally in the Sacred Headwaters region since 1978, serving as the first ranger for the adjacent Spatsizi Provincial Park. He’s married, conceived children, and seen friends live, thrive, and even die on traplines in his time on the land drained by the Stikine, Nass, and Skeena. In 2011, he published The Sacred Headwaters: The Fight to Save the Stikine, Skeena, and Nass. In it, Davis describes the 50-mile lake chain that flows out from Ealue Lake, where he established a family fish camp:

Nine bodies of water altogether, each more beautiful than the next, and all supporting an astonishing wealth of fish and game: rainbow trout in every eddy and stream, moose in the ferns, grizzly and black bears in white spruce forests that skirt the upland plateaus, which nurture populations of sheep and mountain goats as abundant as any known to exist in the world.

But beyond raw wilderness romance, Davis credits the human factor for turning it into a home. He speaks of mapping the Tahltan culture through 25 years of research in the same breath as watching a late-night dinner for one late traveler swell into a feast for 49.

“You grow loyalty to the country as it grows around you,” Davis says. “I was living a whirlwind but Ealue Lake became this well we drank from year after year. It was pivotal to the wellbeing of my family. It’s an exotic home, but through time I learned it wasn’t wild at all. This is really a neighborhood where people came to terms with the land, and because of that there’s a magic to it. No one would take a stick of firewood — if you’re part of the community, you’re part of the community. And they will come together, native and nonnative, to stand up for the land.”

Part 2: Under Threat, Sacred Headwaters' Immune System Kicks In

Part 3: One Battle To Save The Sacred Headwaters Ends, Another Begins

Exploring An Unwelcoming Gem

Exploring An Unwelcoming Gem

EXPLORING AN UNWELCOMING GEM: EXPLORING THE HARSH BEAUTY OF THE CASCADES

By Ted Alvarez Photo by Chris Burkard Originally Published in GEAR PATROL, October 2014

The North Cascades, one of the least-visited national parks in the country, abuts Washington's border with British Columbia, a mere two-and-a-half hours from downtown Seattle. So why doesn't anybody go?

Well, the North Cascades aren't exactly user friendly. There are no drive-up views for the minivan crowd. Plush lodges and charming hamlets are few and far between. Stray kids looking for a gift shop might get swallowed by a patch of thorny devil's club. The price of entry might is almost always steep (literally). Rangers usually spend a lot of time telling you what a miserable time you'll have if you put yourself at the mercy of the park's capricious and violent weather.

But they just want it for themselves. With some grit and serious sweat, adventurers who press through those barriers reap major rewards. you'll see serrated ridges that end at the horizon, the southern toe of a wild country that stretches all the way to Alaska. Sixty percent of all the glaciers in the Lower 48 drape these mountains, making it an alpinist's wonderland. From epic rock routes to 10,000-foot volcanoes, the peaks here are spoken of in reverent tones: Mt. Baker, Liberty Bell, Bonanza, Mt. Terror, the Pickets. The superlatives stretch into the winter, where ski mountaineers and on-site shredders alike rack up blower days in the snowiest places on Earth.

But you don't have to be a technical dirtbag with more climbing hardware than pairs of underwear to enjoy all the park has to offer. Pick a trail, any trail, and just put one foot in front of the other. Before long you'll end up in a big-river valley choked with 200-foot-tall trees and more eagles than you can count, or on a knife-edge ridge covered in blueberries. (And make strategic use of them, like we did in slide 16.) Just go get lost.

National Parks: Denali

National Parks: Denali

NATIONAL PARKS: DENALI

By Ted Alvarez Originally Published in BACKPACKER MAGAZINE, June 2011

I hadn’t planned to get my younger brother and sister killed. But while stuck crotch-deep in the roiling chocolate milk of Denali’s Thorofare River, it seemed a distinct possibility. We found the shallowest spot for miles and grimaced as 40°F water crept up our thighs, grapefruit-size rocks pelted our ankles, and the current sucked at our overstuffed packs. Then my sister stumbled, our locked elbows skimmed the surface, and one clear thought raced through my mind: If we don’t die, our mom is going to kill me.

As every student of wilderness knows, Denali’s rewards—raw Alaska, awe-inspiring wildlife, soul-quieting solitude—are commensurate with the challenges. The bears are as big and fast as Fiats. The peaks are the continent’s highest and coldest. The glacier-ravaged terrain is treacherous. The trails: nonexistent. All of which can make the park’s hallowed backcountry seem as intimidating as it is alluring. But does that make it experts-only? How much experience do you really need? Obviously, beginners shouldn’t tackle Denali alone, but can average hikers rise to the challenge? I planned to prove they could, and I would do it by leading my little brother and sister deep into the heart of the park. But as we teeter in frigid Sunset Creek, I’m thinking Bonnaroo tickets would have been a much better idea.

Like most Denali visits, our adventure begins on the park’s iconic green and white buses, where we cram into rows of sticky vinyl seats. These land whales trundle along the 92-mile park road, the only significant human mark across a Vermont-size swath of tundra, spruce-dense taiga, and moonscape of rock and ice. The buses transport an odd mix of souvenir-sweatshirt-clad tourists and nervous backpackers about to walk into a private slice of the Last Frontier.

Elissa, Jeff, and I—with varying degrees of anxiety—are among the latter. While I chase empty spots on the map and go weeks without shampoo, years of urban living have dulled my siblings’ wild edges. Jeff, 24 and seven years my junior, is the youngest. He’s a Denver recording engineer and drummer, only truly focused when beating the skins in a flurry of octopus limbs. Middle-child Elissa, 28, has honed her honeyed voice into a career as an opera singer in Boston (diva side effects like hotheadedness, impatience, and lack of pity for fools included). Bound by merciless humor, we’ve always felt able to take on the world together and turn it into a big party. After going our own ways as adults in recent years, I hoped we could rekindle that party in Denali. us backpackers about to walk into a private slice of the Last Frontier.

We’d snagged permits to units 13, 18, 23, and 12, a clutch of adjacent zones four hours from the entrance on the park’s north side. Clustered near Mt. Eielson, these units connect river drainages that offer bountiful terrain to wander in, plus the opportunity to adjust itineraries as weather and conditions dictate (flexibility is a key to traveling safely in Denali). Our plan: We’ll follow Glacier Creek, a 11-mile braided river bordering the Muldrow Glacier, picking our way to the crest of Anderson Pass, the only nontechnical notch to drill into the core of the Alaska Range. At the top, we’ll gape at a black-granite Valhalla draped in Crest-blue ice. En route, we’ll cross trackless tundra benches and see glaciers the size of entire Lower 48 counties. In short, I’ve devised a crown-jewel route—pointedly ignoring my siblings’ inexperience—that promises high adventure (or shared misery). As their big brother, it’s practically my duty. Plus, I have a theory to prove.

More Stories

More Stories

SURVIVAL LAB

By Ted Alvarez Originally Published in BACKPACKER MAGAZINE

Foraging – March 2013 | VIDEO: Finding Food in the Wild

Bivy Sacks – November 2012 | VIDEO: Building An Emergency Shelter

Finding Water – September 2012 | VIDEO: Harvesting Dew | VIDEO: Build a Backcountry Solar Still | VIDEO: Set up a Transpiration Bag

Signaling Devices – August 2012 | VIDEO: Use a Signaling Mirror | VIDEO: Signaling Devices Roundup

Knives – June 2012 VIDEO: Ultimate Knife Test | VIDEO: Carve a Feather Stick

CLIMATE REFUGEES, DO NOT MOVE TO THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST

By Ted Alvarez Originally Published in GRIST, 29 July 2014

ROCK-SOLID CLIMBING GEAR YOU MUST TRY

By Ted Alvarez Originally Published in MEN'S HEALTH, 21 February 2014

DECODING THE DARK HORSE LEGEND

By Ted Alvarez Originally Published in THE DAILY CAMERA, 13 January 2013

QUEENS OF THE STONE AGE FEELS GOOD ABOUT FOOS TOUR

By Ted Alvarez Originally Published in ROLLING STONE, 29 October 2000